Bluefish

| Bluefish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Scombriformes |

| Family: | Pomatomidae Gill, 1863 [3] |

| Genus: | Pomatomus Lacépède, 1802[2] |

| Species: | P. saltatrix

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pomatomus saltatrix (Linnaeus, 1766)

| |

| Synonyms[4] | |

| |

The bluefish (Pomatomus saltatrix) is the only extant species of the family Pomatomidae. It is a marine pelagic fish found around the world in temperate and subtropical waters, except for the northern Pacific Ocean. Bluefish are known as tailor in Australia and New Zealand,[5] elf and shad in South Africa.[6][7] It is a popular gamefish and food fish.

The bluefish is a moderately proportioned fish, with a broad, forked tail. The spiny first dorsal fin is normally folded back in a groove, as are its pectoral fins. Coloration is a grayish blue-green dorsally, fading to white on the lower sides and belly. Its single row of teeth in each jaw is uniform in size, knife-edged, and sharp. Bluefish commonly range in size from seven-inch (18-cm) "snappers" to much larger, sometimes weighing as much as 40 lb (18 kg), though fish heavier than 20 lb (9 kg) are exceptional.

Systematics

[edit]The bluefish is the only extant species now included in the family Pomatomidae. At one time, gnomefishes were included, but these are now grouped in a separate family, Scombropidae. Extinct relatives of the bluefish include Carangopsis from the Early Eocene of Italy and Lophar from the Late Miocene of Northern California.

Distribution

[edit]

Bluefish are widely distributed around the world in tropical and subtropical waters. They are found in pelagic waters on much of the continental shelves along eastern America (though not between south Florida and northern South America), Africa, the Mediterranean and Black Seas (and during migration in between), Southeast Asia, and Australia. They are found in a variety of coastal habitats: above the continental shelf, in energetic waters near surf beaches, or by rock headlands.[8] They also enter estuaries and inhabit brackish waters.[9][10][11] Periodically, they leave the coasts and migrate in schools through open waters.[4][12]

Along the U.S. East Coast, bluefish are found off Florida in the winter. By April, they have disappeared, heading north. By June, they may be found off Massachusetts; in years of high abundance, stragglers may be found as far north as Nova Scotia. By October, they leave the waters north of New York City, heading south (whereas some bluefish, perhaps less migratory,[13][14] are present in the Gulf of Mexico throughout the year).

In a similar pattern overall, the economically significant population that spawns in Europe's Black Sea migrates south through Istanbul (Bosphorus, Sea of Marmara, Dardanelles, Aegean Sea) and on toward Turkey's Mediterranean coast in the autumn for the cold season.[15] A campaign was launched in Turkiye by Fikir Sahibi Damaklar (Intelligent Palates) to protect the Bluefish. This was reported on in 2013.[16] More recently, it was reported that bluefish near Istanbul were abundant and that there is a fishing ban every year between April 15 - Sept. 1 to preserve fish eggs and ensure sustainable fish farming.[17] Along the South African coast and environs, movement patterns are roughly in parallel.[18]

Life history

[edit]Adult bluefish are typically between 20 and 60 cm (8 in to 2 ft) long, with a maximum reported size of 120 cm (4 ft) and 14 kg (31 lb). They reproduce during spring and summer, and can live up to 9 years.[4][12] Bluefish fry eat zooplankton, and are largely at the mercy of currents.[19][20] Spent bluefish have been found off east-central Florida, migrating north. As with most marine fish, their spawning habits are not well known. In the western side of the North Atlantic, at least two populations occur, separated by Cape Hatteras in North Carolina. The Gulf Stream can carry fry spawned to the south of Cape Hatteras to the north, and eddies can spin off, carrying them into populations found off the coast of the mid-Atlantic, and the New England states.[21]

Feeding habits

[edit]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Adult bluefish are strong and aggressive, and live in loose groups. They are fast swimmers that prey on schools of forage fish, and continue attacking them in feeding frenzies even after they appear to have eaten their fill.[4][12] Depending on area and season, they favor menhaden and other sardine-like fish (Clupeidae), jacks (Scombridae), weakfish (Sciaenidae), grunts (Haemulidae), striped anchovies (Engraulidae), shrimp, and squid. They are cannibalistic and can destroy their own young.[22] Bluefish sometimes chase bait through the surf zone, attacking schools in very shallow water, churning the water like a washing machine. This behavior is sometimes referred to as a "bluefish blitz".[23]

In turn, bluefish are preyed upon by larger predators at all stages of their lifecycle. As juveniles, they fall victim to a wide variety of oceanic predators, including striped bass, larger bluefish, fluke (summer flounder), weakfish, tuna, sharks, rays, and dolphins. As adults, bluefish are taken by tuna, sharks, billfish, seals, sea lions, dolphins, porpoises, and many other species.[24]

Bluefish are aggressive and have been known to inflict severe bites on fishermen. Wading or swimming among feeding bluefish schools can be dangerous.[25] In July 2006, a seven-year-old girl was attacked on a beach, near the Spanish town of Alicante, allegedly by a bluefish.[26] In New Jersey, the large beachfeeder schools are very common and lifeguards report never having seen bluefish bite bathers in their entire careers.[citation needed]

Parasites

[edit]

Like other fish, bluefish host a number of parasites. One parasite is Philometra saltatrix, a philometrid nematode in the ovaries. The females are brownish red and may be as long as 80 mm; the males are very small.[27]

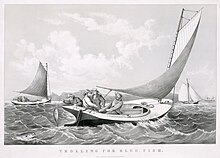

Recreational fisheries

[edit]In Australia, bluefish, called "tailor", are caught on the west coast from Exmouth to Albany, with the most productive fishing areas being in the west coast bioregion.[28]

The IGFA All Tackle World Record for bluefish stands at 14.4 kg (31 lb 12 oz) landed by James Hussey near Hatteras, North Carolina.[29] The unofficial record belongs to Captain Benjamin Dellacono who landed a 35 lb 6oz Blue Fish off the coast of Stonington, Connecticut.

Commercial fisheries

[edit]In the U.S., bluefish are landed primarily in recreational fisheries, but important commercial fisheries also exist in temperate and subtropical waters.[31] Bluefish population abundance is typically cyclical, with abundance varying widely over a span of 10 years or more.[32]

Management

[edit]Bluefish is a popular sport and food fish, and has been widely overfished.[33] Fisheries management has generally stabilized its population. In the middle Atlantic region of the U.S., bluefish were heavily overfished in the late 1990s, but active management rebuilt the stock by 2007.[34] Elsewhere, public awareness efforts, such as bluefish festivals, combined with catch limits, may be having positive effects in reducing the stress on the regional stocks.[35]

Culinary use

[edit]Bluefish may be baked or poached,[36] or smoked.[37] The smaller ones ("snapper blues") are generally fried, as they are not very oily.[38]

Because of its fattiness, bluefish goes rancid rapidly, so it is generally not found far from its fisheries,[37] but where it is available, it is often inexpensive.[39] It must be refrigerated and consumed soon after purchase; some recipes call for keeping it in vinegar and wine before cooking, in vina d'alhos[38] or en escabeche.[40] By the same token, it is high in omega-3 fatty acids, but also in mercury and PCBs,[37] containing the high level of about 0.4 ppm of mercury on average,[41] comparable to albacore tuna or Spanish mackerel.[42] For that reason, the U.S. FDA recommends that young children and women of childbearing age consume no more than one serving per week (a serving size is about 4 ounces uncooked for an adult, 2 ounces for children ages 4–7 years, 3 ounces for children ages 8–10 years, and 4 ounces for children 11 years and older).[43]

References

[edit]- ^ Carpenter, K.E.; Ralph, G.; Pina Amargos, F.; Collette, B.B.; Singh-Renton, S.; Aiken, K.A.; Dooley, J.; Marechal, J. (2017) [errata version of 2015 assessment]. "Pomatomus saltatrix". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T190279A115314064. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T190279A19929357.en. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ Eschmeyer, William N.; Fricke, Ron & van der Laan, Richard (eds.). "Pomatomus". Catalog of Fishes. California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ Van Der Laan, Richard; Eschmeyer, William N.; Fricke, Ronald (2014). "Family-group names of Recent fishes". Zootaxa. 3882 (2): 001–230. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3882.1.1. PMID 25543675.

- ^ a b c d Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Pomatomus saltatrix". FishBase. December 2019 version.

- ^ "CAAB taxon report for Pomatomus saltatrix". CSIRO. Archived from the original on 2010-02-26.

- ^ Heemstra, Phillip C.; Heemstra, Elaine (2004). Coastal Fishes of Southern Africa. NISC (PTY) LTD. pp. 187–188. ISBN 9781920033019.

- ^ "Bluefish Identification". LandBigFish. Archived from the original on 2009-02-27. Retrieved 2009-02-17.

- ^ "New England/Mid-Atlantic | NOAA Fisheries" (PDF). 20 July 2021. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-08. Retrieved 2022-11-13.

- ^ McBride, R. S.; Conover, D. O. (1991). "Recruitment of young-of-the-year bluefish Pomatomus saltatrix to the New York Bight - variation in abundance and growth of spring-spawned and summer-spawned cohorts". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 78 (3): 205–216. doi:10.3354/meps078205. JSTOR 24826553.

- ^ McBride, R. S.; Ross, J. L.; Conover, D. O. (1993). "Recruitment of bluefish Pomatomus saltatrix to estuaries of the U.S. South Atlantic bight" (PDF). Fishery Bulletin. 91 (2): 389–395. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-12-27.

- ^ McBride, Richard S.; Scherer, Michael D.; Powell, J. Christopher (1995). "Correlated Variations in Abundance, Size, Growth, and Loss Rates of Age-0 Bluefish in a Southern New England Estuary". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 124 (6): 898–910. Bibcode:1995TrAFS.124..898M. doi:10.1577/1548-8659(1995)124<0898:CVIASG>2.3.CO;2.

- ^ a b c "Pomatomus saltatrix (Linnaeus, 1766)". FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ^ "Pomatomus saltatrix (Bluefish)". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 2015-11-09.

- ^ "Common Name: Bluefish". Combat Fishing.

- ^ "Saving the Sultan of Fish". Archived from the original on 2011-11-27. Retrieved 2012-11-02.

- ^ "Istanbul does not let go of the tail of its bluefish". Archived from the original on 30 March 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ "Bosphorus witnesses abundance in bluefish - article dated Nov 2023". November 2023. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ "Pomatomus saltatrix". 13 May 2012.

- ^ Norcross, J. J.; Richardson, S. L.; Massmann, W. H.; Joseph, E. B. (1974). "Development of young bluefish Pomatomus saltatrix and distribution of eggs and young in Virginian coastal waters". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 103 (3): 477. Bibcode:1974TrAFS.103..477N. doi:10.1577/1548-8659(1974)103<477:DOYBPS>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1548-8659.

- ^ Ditty, J. G.; Shaw, R. F. (1993). "Seasonal occurrence, distribution, and abundance of larval bluefish, Pomatomus saltatrix (Family: Pomatomidae), in the northern Gulf of Mexico". Bulletin of Marine Science - Miami. 56 (2): 592–601.

- ^ Kendall, A. W. Jr.; Walford, L. A. (1979). "Sources and distribution of bluefish, Pomatomus saltatrix, larvae and juveniles off the east coast of the United States" (PDF). Fishery Bulletin. 77 (1): 213–227. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-08-13. Retrieved 2022-11-13.

- ^ Schultz, Ken (2009) Ken Schultz's Essentials of Fishing. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470444313.

- ^ Honachefsky, Nick (October 2016). "Blues travelers". Outdoor Life. 223: 68.

- ^ "Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch. Bluefish" (PDF). SeaChoice.org. December 12, 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-01-20. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^ Lovko, Vincent J. (2008) Pathogenicity of the Purportedly Toxic Dinoflagellates Pfiesteria Piscicida and Pseudopfiesteria Shumwayae and Related Species[permanent dead link] ProQuest. ISBN 9780549882640.

- ^ "Un depredador rápido y muy voraz con dientes de sierra (in Spanish)" El País, July 14, 2006

- ^ Moravec, František; Chaabane, Amira; Neifar, Lassad; Gey, Delphine; Justine, Jean-Lou (2017). "Species of Philometra (Nematoda, Philometridae) from fishes off the Mediterranean coast of Africa, with a description of Philometra rara n. sp. from Hyporthodus haifensis and a molecular analysis of Philometra saltatrix from Pomatomus saltatrix". Parasite. 24: 8. doi:10.1051/parasite/2017008. PMC 5364780. PMID 28287390.

- ^ "Tailor recreational fishing". fish.wa.au. Government of Western Australia. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ "Bluefish". igfa.org. International Game Fish Association. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ Based on data sourced from the FishStat database Archived 2012-11-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Bluefish_ Status of Fishery Resources off the Northeastern US". NOAA. 20 July 2021.

- ^ Ulanski, Stan (2011). Fishing North Carolina's Outer Banks. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807872079.

- ^ Ceyhan, Tevfik; Akyol, Okan; Ayaz, Adnan; Juanes, Francis (2007). "Age, growth, and reproductive season of bluefish (Pomatomus saltatrix) in the Marmara region, Turkey". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 64 (3): 531–536. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsm026.

- ^ "Bluefish". FishWatch. NOAA. Archived from the original on 2015-10-08. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ^ "Istanbul Celebrates New Hope for a Favorite Fish With First-Annual 'Lüfer Festival'". Treehugger.

- ^ Davidson, Alan (2002). Mediterranean Seafood (3rd ed.). Ten Speed Press. p. 100. ISBN 1580084516.

- ^ a b c Hunt, Kathy (2014). Fish Market: A Cookbook for Selecting and Preparing Seafood. Running Press Adult. p. 87. ISBN 978-0762444748.

- ^ a b Davidson, Alan (1980). North Atlantic Seafood. Viking Press. pp. 92–93. ISBN 0670515248.

- ^ Sifton, Sam. "Smoked Bluefish Pâté". New York Times.

- ^ "Florence Fabricant, "Bluefish Escabeche", New York Times Cooking".

- ^ Burger, Joanna; Gochfeld, Michael (2011). "Mercury and selenium levels in 19 species of saltwater fish from New Jersey as a function of species, size, and season". Science of the Total Environment. 409 (8): 1418–1429. Bibcode:2011ScTEn.409.1418B. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.12.034. PMC 4300121. PMID 21292311.

- ^ "Mercury Levels in Commercial Fish and Shellfish (1990-2012)". FDA. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ Program, Human Foods (5 September 2024). "Advice about Eating Fish". U.S. Food & Drug Administration.

Further reading

[edit]- "Pomatomus saltatrix". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 30 January 2006.

- Bluefish Archived 2015-10-08 at the Wayback Machine NOAA FishWatch. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

External links

[edit]- Bluefish or Tailor video on Youtube

- Tailor in Australian Marine Reserve on Youtube

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Family Pomatomidae". FishBase.

- "Bluefish" at the Encyclopedia of Life

- Life history of the bluefish

- Photo of a large bluefish

- Fisheries Western Australia Tailor Fact Sheet

- Bluefish feast in Italy